Lectio Divina | A Reflection on Yehuda Amichai's "The Amen Stone"

It took me a week to finally choose a poem I resonated with among the six poems I was assigned to reflect on through the ancient practice of sacred reading called lectio divina. The experience of being in a writing course (albeit online) has given me the liberation to explore the power of words and unearth the gift I know I've long locked within. The gift of realizing I have the same power as well.

My writing process was a painful unraveling. I could not write immediately. I could not catch the thought and pin it down on paper. I tried reading other books that would get the flow of creativity going and to no avail the anxiety caught on and forced me to take a break. So I did. And went back on it again this weekend. I had to recalibrate my mind for 2 hours. Removing the residue of the business mind that forces me to constrict my definitions of life in a less human sounding voice. I began my meditatio of Yehuda Amichai's "The Amen Stone".

On my desk there is a stone with the word “Amen” on it,

a triangular fragment of stone from a Jewish graveyard destroyed

many generations ago. The other fragments, hundreds upon hundreds,

were scattered helter-skelter, and a great yearning,

a longing without end, fills them all:

first name in search of family name, date of death seeks

dead man’s birthplace, son’s name wishes to locate

name of father, date of birth seeks reunion with soul

that wishes to rest in peace. And until they have found

one another, they will not find a perfect rest.

Only this stone lies calmly on my desk and says “Amen.”

But now the fragments are gathered up in lovingkindness

by a sad good man. He cleanses them of every blemish,

photographs them one by one, arranges them on the floor

in the great hall, makes each gravestone whole again,

one again: fragment to fragment,

like the resurrection of the dead, a mosaic,

a jigsaw puzzle. Child’s play.

- translated by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld (Harcourt, 2000)

Half a Saturday I let his words sink in and take hold of me until I became quite troubled and burdened as if I'm pregnant with its meaning. So then began my journey into oratio and unveiling for me what his words mean.

This is what I wrote early this Sunday morning. An attempt to unlock the long barred room where the writer in me weeps to be called free.

"The Amen Stone"

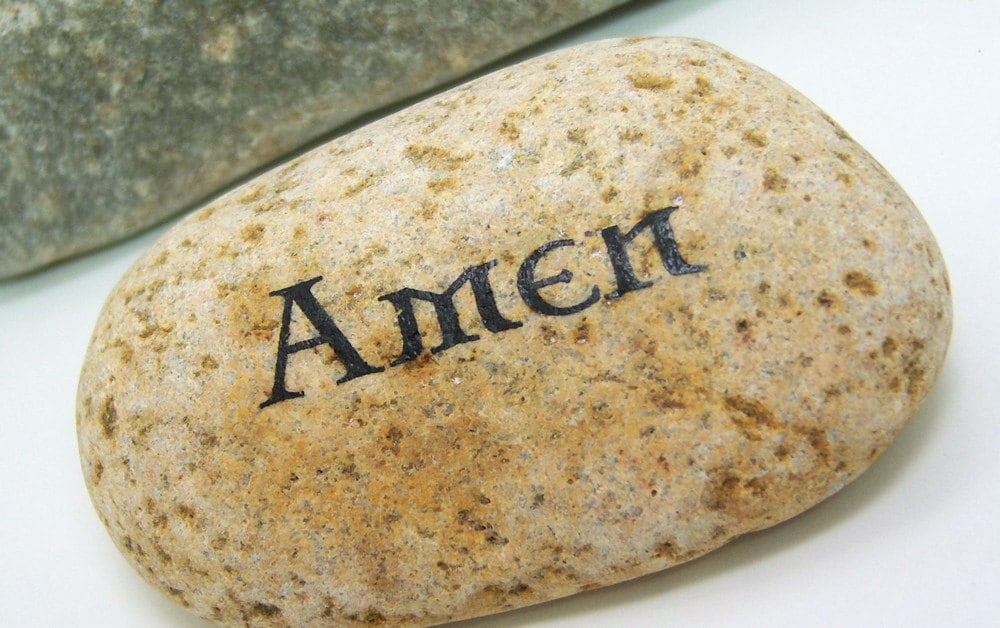

Yehuda Amichai lifts the curtain on a story that is familiar to most who try to keep up with the struggle of human life. He opens up the poem with a big sense of recollection. Like he was deep in thought holding a million memories. Sorting out a haunting experience that seems to never stop being on a playback loop in his mind. He starts with—“On my desk there is a stone with the word, ‘Amen’ on it.”—where he brings the reality of this memory he wishes to come to terms with. It is a strong statement coming from a soldier who fought in four armies and who perhaps have witnessed too many deaths and longs to understand what it means to stay alive after it all.

The number of years this stone has lasted has been “many generations ago” from a “Jewish graveyard destroyed” insists that the poet’s memory is greatly significant and must be known to all. It feels like a raised banner marking a territory of a sacred place saying: all who enter must kneel with respect for this place is sacred ground. Perhaps at that time the poet thought there was too little recognition of the real destructiveness of war and how lives are affected in the end when all is left are torn down war-ruins and blood stained sidewalks. He tells of how there are many more stones like this that have been “scattered helter-skelter” and how these “stones” now sound like they’re not just mere concrete but they are a million more memories of lives ruined because of the insane decisions that have been made to initiate a call to war. It feels like a silent scream resounding over the noise of conflict created by the tumultuous clashing of human beliefs because of a lacking desire to understand and to make peace.

Yet this becomes the most painful call to realization from a poet to a reader as he points out saying “and a great yearning, a longing without end, fills them all.” There is a point the poet wants to emphasize: war does not give us the answers that we need. Then he moves on and surveys the reasons why. He enumerates what becomes lost when we go into war and tells of the endless search for answers that begins the haunting of memories that knows no end.

“first name in search of family name, date of death seeks

dead man’s birthplace, son’s name wishes to locate

name of father, date of birth seeks reunion with soul

that wishes to rest in peace.”

He draws us into the irony of how the anger that propels one to come to war with another only leaves oneself destroyed and lost. An indignant cry that proclaims,

“and until they have found one another, they will not find perfect rest.”

I say indignant because it feels the poet speaks from a voice of regret and an aching for resolution. He served in the war for a reason he no longer believes to be true today as he sits on his desk gazing at the stone “with the word ‘Amen’ on it”. So he, as haunted as he is, wants to come to terms with why the war has happened in the first place, why this memory does not bring him peace and why this particular stone that sits on his desk has the word “Amen” written on it.

Who could have written the word “Amen”? Was it passed down from a generation to another generation written by a blood-stained soldier’s hand realizing his fellow platoon mate had just saved his life after the grenade blasted his head away? Was it his hand that wrote the word “Amen”? Did he write it a while back? Did he write it just now? These questions are significant and bring the reader into a reflection of how strong the memory of the poet is. It shows the intensity of these emotions contained on that one word engraved in a stone fragment of a “Jewish graveyard destroyed.”

Nothing can be as intense as the word Amen when we try to affirm and confirm what we comprehend from a seemingly senseless situation like the damage of war. Only the word Amen describes an understanding that knows no limit. Only the word Amen can be uttered or written when this understanding has been moved by the peace that surpasses and goes beyond the natural world we see and touches the space of the Unseen. I’d like to think that the word “Amen” was written just a few days before the poet sat down on his table and chose to make the decision to come to terms with the haunting of memories. And through his writing births this poem that has become the instrument he used to find the answers he has been looking for.

“But now the fragments are gathered up in lovingkindness

By a sad good man. He cleanses them of every blemish,

Photographs them one by one, arranges them on the floor

In the great hall, makes each gravestone whole again,

One again: fragment to fragment,

Like the resurrection of the dead.”

I’d like to think that the “sad good man” the poet refers to in the stanza above is God. For only God can gather broken pieces of lives tattered by the decisions made in a world of seemingly unending conflict and look at these lives with “loving-kindness” and still have the genuine desire to move His hand and “cleanse them of every blemish”. Only God can restore what seems to never be restorable.

Experiencing the poem of Yehuda Amichai for me brings me to resonate with the strength of how he as a poet unearthed and mustered the choice to make a decision and search for the answers that will quiet his unrest. For him it was a war he battled against countries. For me it is a war I battle within myself. The battle I waged with my world that threatened to define who I was, how I should be and how should I survive. And I engaged in this battle by fighting back the way I was expected to. Arming myself with weapons that taught me how to think and fight and exist in defined reality that is not my own. Journals and lose leaves of paper have been kept in boxes and on my shelves came to replace books that taught me the language of profit and money and business empires. And now I look at the remains of how this struggle kept on clashing two parts of my life. And I feel that “great yearning and longing without end”.

As I journeyed with this poem through lectio divina I have come to a realization and a remembering that the reality of life in this world does exist with conflict but it does not have to be overcome by it. That the more conflict one experiences, the more the “sad good man” is moved with “loving-kindness” and keeps on moving his hand over the stones of broken and fragmented dreams and “cleanses them from blemish”. The more questions raised in endless searching, the more the “sad good man” comes to answer and moves the “stones” in graceful patterns to complete the mosaic he photographs to perfection. The more we feel like entering another death of a dream or a forsaken longing or another lost gravestone, the more the “sad good man” finds reason to gather the “stones” and “arrange them on the great hall” to “make each gravestone whole again, one again”. And so it is that our lives become an endless resurrection and an endless revival under the hands of the “sad good man”.

The poet reminds me that there is a face of God existing very close and very near especially in times of great conflict. He is the “sad good man” that walks tenderly over our brokenness and longing. His tenderness feels like an emotion felt by an old grandfather and a young innocent child at the same time. The hands that gather the “stones” and arrange them in the “great hall” are hands of a skilled Maker who knows what he is doing. The hands that patiently work through “fragment to fragment” of the jigsaw puzzle and smiles at the mosaic become the wonder of a child at play. It is this paradox of feeling that makes conflict easier to deal with once we know how to sit with it.

Once we know, then it becomes easier to surrender so that the peace that surpasses all understanding is allowed to rest on our longings, and finally hold with a strength that trusts and believes in the “loving-kindness” of the “sad good man”, our fragmented stone and a pen that can write on it the word “Amen”.

Words are flowing. :) This is beautiful, Kathy.

ReplyDeleteKathy, thanks for sharing! This is very insightful. You really opened up to the poem for me. The short lines seem to extend infinitely because what you wrote made me see the meanings that the poem can hold for someone like him, a soldier in old wars, and you in your personal "battles" and for every other reader who comes across this poem. I especially like your insights about the "sad good man" as being God in our lives. I like reading something that surprises me at every paragraph, when I cannot predict insights I will read next. This is certainly one of those. And your tone matches the poem. It has a very gentle, caressing manner, like the stone was in front of you the whole time. Thank you! :)

ReplyDeleteThank you Rachel. :)

ReplyDeleteHi Marie! Oh so glad you came for a visit. :) Thank you for encouraging me to keep writing. Yes, I was indeed trying to imagine the stone was right infront of me. I was actually so glad to see that I found a picture suitable for it when I went on Google. I miss your writing and I hope to read some of your words soon too.

ReplyDeletevery beautiful indeed!... i wish i can do justice with the words that i use like you do Ms. Kathy. i didn't understand the poem at first, but then as you slowly dissect each line, it's as if i have been transported in a time & place where everything had happened. it's as if i had born witness to the pain and longing felt by the owner of that stone. it's as if i became a part of something that was totally alien to me. your words flowed like a stream at its most quiet moment... and yet, at its deepest! :)

ReplyDeleteHi Susan! Wow. Thank you for your kind words. I don't know what to say. I just feel grateful that you are one of those who keep on encouraging me to keep writing and I'm really glad that you're part of this journey with me too. I don't really take notice of how my writing affects other people. Most of the time I just let it happen and let their comments pass me by. Perhaps it's my insecurity. Perhaps it's my fear in facing how much I truly want to keep writing and respond to this vocation that I'm not able to hold the kind words people say about my thoughts on a page. It's that kind of fear that happens to you because you want it that bad. :) But you are one of those who help me face this fear. Thank you so much!

ReplyDelete"You really opened up to the poem for me." Oops, I meant to say you really opened up the poem for me, if that makes more sense :) Still not back to writing. Will let you know if I do write anything again :)

ReplyDeleteGot it Marie. :) Will be looking forward to reading your work again soon.

ReplyDelete